Separately Managed Account

Dec 02, 2025|ByFrances WalshPatrick Geddes

How taxes reshape asset allocation:

- Traditional asset allocation historically has underestimated the effect of taxes, which can radically alter the risk and return potential for taxable investors

- To highlight this issue, research has shown how much the asset allocation of a tax-exempt entity like many university endowments changes once the impact of taxes are reflected

- Different strategies look very different once the impact of taxes is considered, especially for public equity, where the hurdle is higher for active alpha in taxable accounts, and direct indexing can add value

In the early 2000’s, the success of the endowment model, particularly Yale’s version, drew interest from advisors and high-net-worth (HNW) investors due to its relative success in driving returns (Over the past 20 years, Yale's endowment has returned an annualized 10.3%, exceeding the median 20-year return for universities by 3.0% per annum)1. Following Yale’s approach, investment professionals began increasing their allocations to alternatives to access potential benefits of the illiquidity premium. However, as a tax-exempt entity at the time,2 Yale’s endowment faced a vastly distinct set of circumstances from those of a taxable HNW investor.

The optimal asset allocation for Yale’s endowment changes drastically in the presence of the tax rates paid by HNW investors, as strategies that tend to generate more taxable income like active public equity, private credit and hedge funds may be emphasized less in a taxable portfolio. On the other hand, strategies that tend to defer income or are taxed at lower rates like funds (especially index exchange-traded funds (ETFs)), may be emphasized more. Direct indexing accounts that generate capital losses provide taxable investors with greater latitude to invest in certain tax-inefficient asset classes or strategies and thereby potentially allow for greater portfolio diversification.

An article from 2015 in Financial Analysts Journal, “What Would Yale Do If It Were Taxable?” explained a way to adjust Yale’s asset allocation for taxes through a three-stage process grounded in the seminal works of Harry Markowitz and Bill Sharpe:

- Determine pre-tax expected returns from the Yale endowment’s asset class weights using a technique known as reverse optimization

- Apply a “tax haircut” to generate after-tax expected returns for each asset class (empirically derived, if possible, though data may not be available for all asset classes)

- Re-optimize weights using after-tax expected returns

However, this research should not be viewed in isolation. An asset class whose expected return is substantially diminished by a tax haircut may earn a place in an optimal after-tax asset allocation as a diversifier. For example, alternative investment funds (such as hedge funds) that are truly uncorrelated with other asset classes may still be included.

The research clearly demonstrates that it is ineffective to treat taxes as an overlay after the “real” pre-tax investment decision process. Rather, it is critical to incorporate tax considerations from the beginning and at every stage of portfolio design, as laid out in the following steps.

Two-step implementation guide to after-tax portfolio design

Step 1: Asset Location – understand implications of account types

Understanding tax implications across the three primary account types—Taxable, Tax-deferred, and Tax-exempt—is essential for after-tax portfolio design. Taxable accounts, such as brokerage accounts, are subject to tax on capital gains as high as 23.8% and tax on ordinary income as high as 40.8%. State taxes can increase these rates even higher. For high-net-worth clients, the largest portion of their investable assets tend to sit within taxable accounts. Meanwhile, tax-deferred accounts like Traditional IRAs and 401(k)s are funded with pre-tax dollars and taxed at ordinary income rates upon withdrawal. And finally, tax-exempt accounts such as Roth IRAs are funded with after-tax dollars and allow for tax-free growth and withdrawals.

After understanding the percentage of assets that sit across these three account types, the next step is to prioritize the vehicles & asset classes to place in each while keeping a total account view.

Step 2: Vehicle & asset class selection – prioritize more tax-efficient wrappers & asset classes in taxable accounts

With an understanding of where to house assets, investors can then allocate within each account. For taxable accounts, investors often prioritize passive or tax-advantaged equity strategies. ETFs provide tax-efficient exposure, which is due to their creation and redemption mechanism. Direct indexing separately managed accounts (SMAs) that focus on tax-loss harvesting can offer the added potential to improve after-tax return by offsetting current and future gains from elsewhere in a portfolio, such as those from the sale of an asset. Key considerations include the investor’s tax bracket, the type and amount of capital gains, and whether assets will eventually be liquidated or passed through an estate. Additional strategies for taxable accounts include private equity, which carries a high probability of long-term gains, and municipal bonds, which can provide tax-free income depending on the investor’s state and tax bracket.

For tax-exempt accounts like IRAs, 401(k)s, or Roths, investors can take advantage of high-return strategies that would otherwise generate significant taxable gains. These include private credit, where distributions are typically taxed at ordinary income rates in taxable accounts, and active equities with tactical or high-turnover approaches that may generate significant gains. Note that active equity ETFs may offer better tax efficiency than active SMAs or mutual funds.

For illustrative purposes only. Comparison of investment account types—Taxable, Traditional IRA, and Roth IRA—showing their tax status and the types of assets best suited for each, ranging from tax-efficient strategies to income-focused and high-return allocations.

Other Considerations for High-Net-Worth Clients

As your clients’ wealth grows, investing often becomes more complex as an increasing portion of assets may be held in taxable accounts, thereby making a tax-efficiency more important.

Concentrated stock: For clients with concentrated positions, strategies such as options overlays and long/short SMAs can help to manage risk and potentially minimize tax burdens.

Trust Structures: Tax-efficient structures offer additional levers to manage after-tax asset allocation. For example, Charitable Remainder Trusts (CRTs) can help defer capital gains and Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts (GRATs) can help transfer assets while managing for taxes.

An example of how BlackRock can help design after-tax solutions

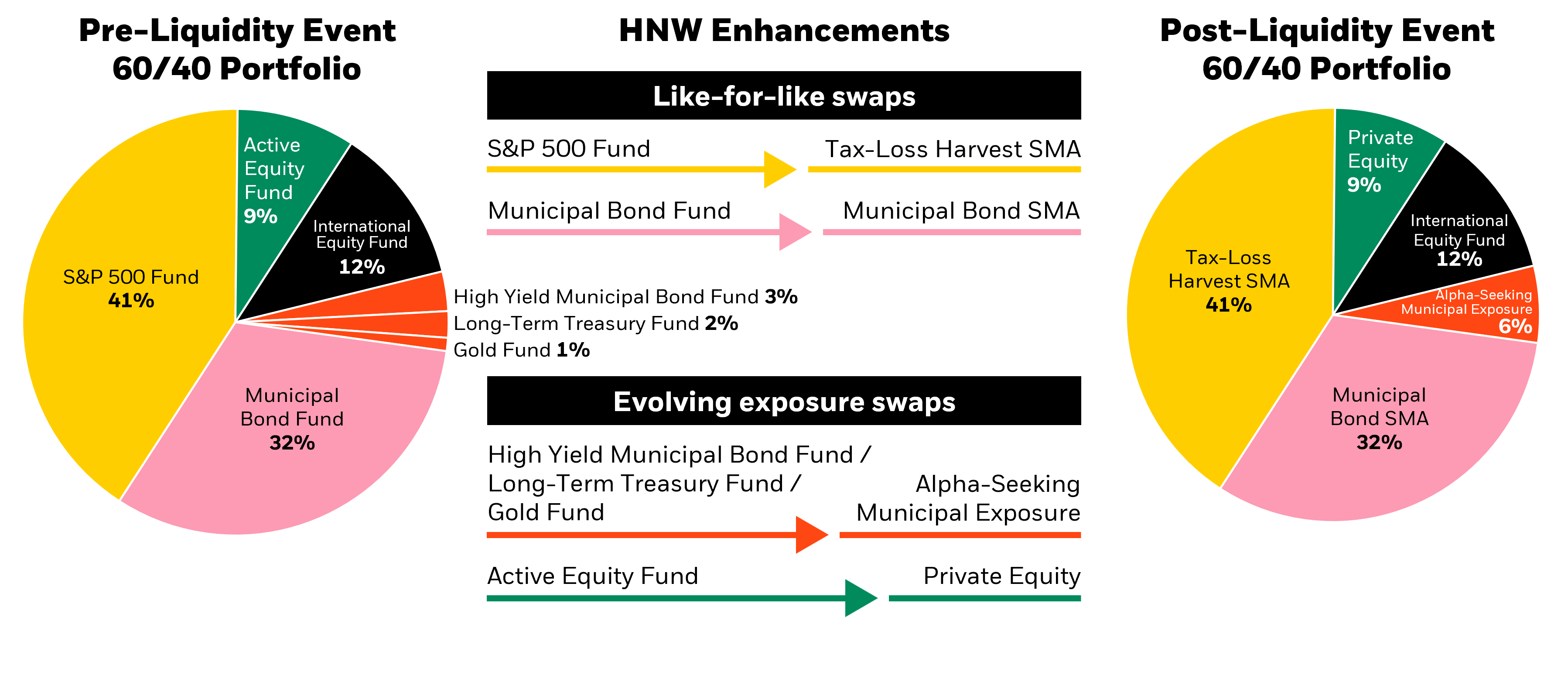

Consider a hypothetical client who had previously been invested in a non-qualified 60/40 portfolio of public investments. When this client sold their business for $10 million, their portfolio needed to evolve to meet their new financial needs. The client, a business owner, expressed that growth was the most important consideration at this point in their financial journey. Liquidity was not a concern for them, and they had another business sale coming up, which made them interested in banking losses to offset future gains.

To address the client's needs, the advisor employed a methodology for high-net-worth portfolio enhancements. This involved a like-for-like approach, where the funding source was highly correlated or had similar risk factors to the destination allocation. Additionally, the advisor thought about evolving exposures, where the funding source had similar levels of risk and volatility to the destination's allocation, potentially giving up liquidity for higher return potential.

For this business owner, the advisor recommended a combination of direct indexing SMA, municipal SMAs, a municipal interval fund, and a private equity fund. These solutions were tailored to provide the necessary growth while considering the client's tax sensitivity and future liquidity events.

For illustrative purposes only. An example of how a moderate aggressive portfolio of public investments might be modified with the addition of private and more tax-efficient investments to potentially be more suitable for a high-net-worth client where taxes are often more emphasized and liquidity is often less emphasized.