BLACKROCK INVESTMENT INSTITUTE

Managing the net-zero transition

The transition to decarbonize the world is happening. Understanding how the journey will unfold in years to come has never been more important for companies and investors alike.

Planning for decarbonization

Planning for long-term decarbonization is challenging, especially at a time of convulsions in the energy sector. Booming demand in the powerful restart of economic activity and snarled supply have driven up prices of fossil fuels and their producers. This is happening even as companies, financial institutions, and governments seek to redouble their efforts to accelerate decarbonization to mitigate climate risk. For investors, the resulting picture can be confusing.

Indeed, the path ahead is deeply uncertain and uneven, with different parts of the economy moving at different speeds. The transition will rewire economies, fundamentally reallocating resources. This process will bring value creation — and destruction. Spurred by government, consumer and investor actions, many companies have already started to transform their business models.

A gradual and orderly transition will help mitigate pressure points that could disrupt economic activity and drive up inflation, in our view. This will allow time to make the necessary investments, phase out carbon-intensive activities, redeploy workers, and develop new technologies to power the net-zero economy.

What will it take to transition?

A rewiring of the global economy

A massive reallocation of resources lies at the heart of the transition to a net-zero world. Fundamentally it is a rewiring of economies, with similarly transformative effects as the integration of China into the world’s trading system or the tech revolution.

We see three main drivers powering the transition: 1) Consumer and investor preferences for greener services, products and assets; 2) Capital costs of incumbent and new technologies: evolution of energy prices; innovations and 3) Climate-specific policies and broader energy, industrial, infrastructure and land use policies. See the graphic.

Source: BlackRock Investment Institute, Feb. 1, 2022. Notes: For illustrative purposes only. Subject to change without notice.

Companies and asset owners must make decisions about how to respond to these drivers. Companies must decide how to alter business models, where to invest and what operations to phase out. Asset owners and managers must decide how to put capital to work and use their shareholder votes with the aim to guard their or their clients’ long-term interests.

We see this interaction between companies and asset owners shaping the transition – and transforming businesses and portfolios.

The result? A rewired economy. Supply and demand will shift, not always in tandem. Capital will be created and redeployed. The reallocation of resources will ultimately be huge, we believe. An example: The world would need to cut global emissions in half by 2030 to achieve net zero by mid-century.1 That’s a 7% annual reduction, we calculate, the type of decline the world only managed in 2020 by freezing much of the global economy when the pandemic hit.

At least one out of 50 employees worldwide will move sectors by 2050 as part of this reallocation.2 And that’s before taking into account those who will move within sectors as some companies thrive and others become challenged. We expect this reallocation to create and destroy company cashflows, reprice assets, and reshape the macroeconomy.

This is a tough adjustment to manage. We see a risk that resources and demand become misaligned through the transition, driving up inflation and causing economic disruption. Companies and investors need to manage this macro risk on top of the other changes triggered by the transition’s drivers.

The transition in motion

Companies are overhauling business models, and we see a repricing of assets across the board. A smooth transition should lead to higher inflation and growth; a disorderly one heralds price spikes and growth disruptions.

Drivers in motion

We are seeing expanding climate policies and regulations, rapid technological advancements and fast-changing societal attitudes. And this will shape cashflows, risks and capital costs for years to come. As a result, it’s crucial companies and asset owners form a judgement on how the transition will further unfold, and reposition their businesses and portfolios accordingly.

There’s been a sea change in how countries, companies and financial institutions view climate change in just a few years. Nearly 90% of the world economy now has net-zero commitments, while about half of major companies and financial institutions do. See the chart. For example, the number of companies setting greenhouse gas reduction targets has accelerated.

Sector transformations underway

The transition is transforming the key energy sector. Renewables generation and electric vehicles are fast gaining market share, and hydrogen projects to decarbonize carbon-intensive industries are mushrooming.

How is this playing out across the corporate landscape? We see the largest effects and risks in the utilities, energy and energy-intensive industrial sectors. Changing production costs, including possible CO2 taxes, and demand are reshaping cash flows and terminal values.

We see the transition driving financial risk in sectors and regions at different speeds. Why? The changes in cost and demand affect sectors differently due to differences between policy, pricing power and the cost of eliminating a unit of carbon. Climate policies can target specific sectors, so the impact varies greatly. Some sectors can more easily pass on increased input costs. And the availability and cost of low-carbon technologies vary by sector.

Assets are repricing

Past performance is no guarantee of current or future results. Forward looking estimates may not come to pass. Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from the Center for Research on Security Prices, Feb. 1, 2022. Notes: To estimate climate-driven repricing, we attribute historic returns to two drivers: cashflow news and discount rate (DR) news. We then identify the DR news associated with climate change using carbon emission intensity (CEI) as a proxy. To isolate the DR component of returns, we apply the standard decomposition formula of Campbell (1991) using a standard factor model of expected returns (which embed well-known predictors such as value, momentum, and quality). Attribution to climate scores is then given by forecasting regressions of DR news on a measure of CEI. Sector returns are MSCI US Sector index-weighted averages of stock-level returns. Green represents the technology sector, the most “green” in our work, while the utilities sector is the most “brown” in the repricing. The 2016-2019 bars represent the total repricing over that period; and the 2021-2025 expectation is the cumulative repricing we expect over this period. The estimate is highly uncertain and are based on factors including risk premia impacts for other long-run transitions such as demographic trends, market pricing of green bonds, and investor survey data on how much return they would be willing to give up to for more sustainable assets. See Sustainability: the tectonic shift transforming investing of February 2020 for details.

The transition’s complex interplay between companies and asset owners is not just changing company fundamentals; it’s also changing valuations. We theorized in 2020 that this would happen – now we have evidence.

We find that carbon-emissions intensity, a key metric of our climate-aware return assumptions, helps gauge expected returns. Relatively green sectors such as IT and brown ones such as utilities experienced a positive and negative repricing in 2020, respectively. See the middle bars in the chart. Our analysis finds this relationship is new as the effect was negligible in the period 2016-2019 (the left bars). We also find the repricing is taking place between and within sectors. We expect more repricing in the next four years.

The macro impact

Forward looking estimates may not come to pass. Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute, Banque de France, International Energy Agency, OECD, Feb 1, 2022. Notes: The bars show the overall estimated impact of three factors –avoidance of climate damages (positive), green infrastructure spending (positive) and costs associated with the transition (negative). The black line shows the estimated net impact. Our estimates of the impact under a climate-aware scenario are based on expected changes in energy consumption including composition, relative carbon and renewables pricing and on potential losses due to global warming. Energy consumption is estimated as a function of GDP and the relative price of energy per the Banque de France's working paper no. 759 titled the Long-term growth impact of climate change and policies. GDP losses from global warming are calibrated on analysis of Impact Assessment Modelsper W. Nordhaus and A.Moffat (2017). We assume green infrastructure spending programs of 1% of GDP gradually phased out over the next 10 years.

The huge reallocation of resources in the transition will transform the macro environment. Will it hurt growth and be inflationary? Compared with the past, yes. But we believe the rear-view mirror is irrelevant for what’s ahead.

Today’s damage from extreme weather events is only a small fraction of the likely global economic disruption we are tracking toward under current policies, in our view.

This could even include famine, mass migration and resource wars.

The avoidance of such climate-related damages and green infrastructure spending far outweigh transition costs, we estimate. An orderly transition should result in a 25% net gain in global growth by 2040, we believe, compared with doing nothing or a disruptive transition. See the chart.

We believe the most effective way to contain inflation and maintain growth is to ensure the transition is gradual. Supply and demand would keep pace, and necessary investment would have time to take place. A disorderly transition, by contrast, raises the risk of supply-demand mismatches, inflation spikes, growth disruptions, and stranded workers, communities and assets.

The transition in practice

The transition’s path is deeply uncertain, making it crucial to manage its risks and opportunities. We show how companies and investors can navigate, drive and invent the transition, zooming in on the energy sector.

Navigating transition uncertainty

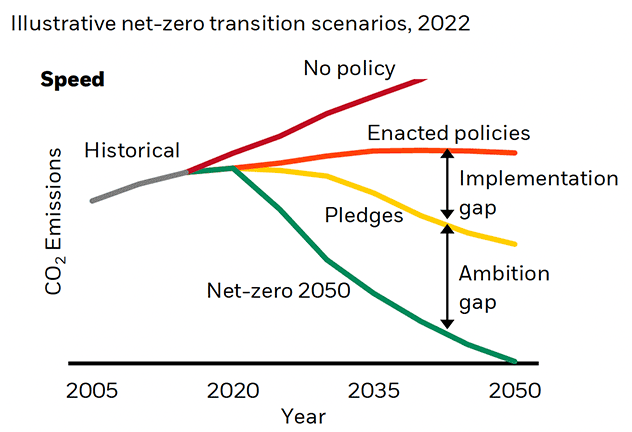

Source: BlackRock Investment Institute, Feb. 1, 2022. Notes: The diagram above serves as a general summary and should not been seen exhaustive nor construed as investment advice. The chart describes how quickly the economy reaches net zero. The implementation gap is the difference between current policies and pledges; the ambition gap is the difference between pledges and the goals of the COP 21 Paris Agreement. For illustrative purposes only.

Government commitments are now nearly universal, yet not enough to deliver net zero by 2050. Already enacted policies are even further behind, creating an “implementation gap” between current policies and pledges and an “ambition gap” between pledges and the goals of the COP 21 Paris Agreement.

Will governments close these gaps? Could they even backtrack? New elections could bring new approaches. A focus on the short term could start to crowd out climate considerations. The answers to these questions are crucial to the transition’s path, or how fast (see the chart) and smoothly carbon emissions are reduced to net zero. The transition’s shape is also key and ranges from smooth to abrupt amid an eventual rush to decarbonize.

The need for tools

How should companies and asset owners go about this? First, they need data, models, analytics and tools at a granular level as they become available. Navigation requires an increasingly precise map over time. Second, companies and asset owners need to act on the views they have developed with the help of these new insights.

Two principal navigation approaches have been used at scale: removing individual companies or sectors viewed as not aligned with the transition (screening), and over- or underweighting companies based on static, backward- looking Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) metrics. We think asset owners can do more to effectively navigate the transition:

- Measure transition readiness — investors can use forward-looking indicators, like emissions targets or other data sources that give insight into how issuers are progressing along several ESG dimensions and positioning themselves for the future.

- Stewardship — corporate engagement and the use of shareholder votes can help make sure portfolio companies properly manage transition risks.

- ESG integration — using transition metrics throughout the investment process can help ensure that even portfolios without a climate focus are managing their transition risk.

Navigation in the energy sector

Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute and IEA, Feb. 1, 2022. Notes: The chart shows estimated growth changes in energy consumption by source under different scenarios outlined in the IEA World Energy Outlook 2021. Current policies represent the changes resulting from stated policies. The pledges scenario shows changes if governments implement pledged changes to consumption. The IEA’s net-zero scenario shows the estimated change needed to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

The energy and utilities sectors face perhaps the starkest challenges and have long had the difficulty of planning for long-term capital assets in an uncertain policy and resources landscape. The drivers of the transition - rapid technological change, shifting consumer preferences and a wide range of policy outcomes - are magnified in this space.

If the world wants to reach net zero by 2050, the use of coal, gas and oil needs to decline at a much faster clip than it would under current policies or pledges. Renewables offer the mirror image. See the chart. We see government policies as crucial for a smooth transition. As years pass without translating commitments into sufficient action, the transition path becomes steeper and more disruptive

Going from shades of brown to green

Forward looking estimates may not come to pass. Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from IEA, Feb. 1, 2022. Notes: The chart shows historical and estimated capex needs by energy sector under different policy paths. See the IEA World Energy Outlook 2021 report for details.

Navigating the energy sector is tough as even relatively small changes can prove very disruptive. The powerful economic restart after the COVID shutdowns exposed mismatches in supply and demand, providing a glimpse of what a disorderly transition could look like. Geopolitical factors and weather-related supply disruptions exposed the underlying fragility in power markets. The result: surging energy prices.

It’s only natural that energy stocks rally. We think it’s impossible to kickstart growth today without fossil fuels. The economy has not been rewired and this will take time. Along the transition, we see periods when the traditional energy sector can benefit from mismatches in supply and demand. This speaks to a mismatch in investments.

Driving and inventing net zero

Some companies and investors want to go beyond navigating the transition to drive it forward or even help invent it. This requires massive amounts of capital from investors and the public sector. This would require $125 trillion flowing into low-carbon energy, a quarter of this investment, or $32 trillion, is needed by 2030. See the chart below.

Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, Feb 1, 2022. Note: The charts show the estimated capex needed across economic sectors and actors by 2030 to be on track for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, according to Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero.

Key players

Governments

Public investment will be needed to de-risk private capital, especially in emerging markets (EMs). Climate change is a global problem. Without a successful transition to net-zero everywhere, climate risk is unmanageable anywhere. The problem: There’s a mismatch of resources in EMs, with too little capital to address growing populations and CO2 emissions. We estimate EMs will need at least $1 trillion per year to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 – more than six times current investment.

Companies

For companies, to drive the transition means proactively revamping business models and to invent it can take the form of funneling research and development funds toward new technologies. A utility producer might phase out a coal-fired power plant and invest in grid-scale battery technology. A steel producer might replace traditional blast furnaces with electric arc furnaces. An automaker might commit to all-electric vehicle platform.

Investors

For investors, to drive means identifying opportunities in companies making these changes. Investing in early-stage technologies is about helping invent the net-zero economy. Dialogue between companies and investors on transition plans and capital needs is crucial to delivering the capital to the right places at the right time, in our view. This goes beyond channeling capital to companies with green business models, we believe, and includes funding carbon-intensive companies leading decarbonization within their industries. Withholding capital or divesting from these firms is counterproductive to the transition, in our view.