Defined

Contribution

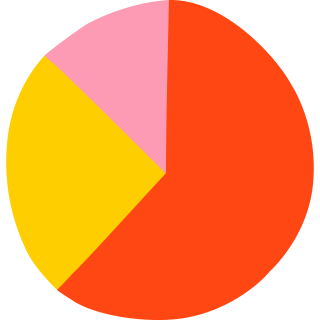

A leading defined contribution (DC) investment-only provider

BlackRock manages the pensions savings, on behalf of our clients, for over 12 million people in the UK. We believe that people deserve financial security across their lifetime, and that retirement should be within reach for everyone.1

1BlackRock as of 31 December 2024.

Unlocking private markets for UK Defined Contribution Schemes

Vidy Vairavamurthy, Managing Director and Chief Investment Officer for the alternative portfolio solutions team within multi-alternatives, discusses the key considerations for schemes integrating private markets into default strategies.

We advance sustainable investing because our conviction is it delivers better outcomes for investors

Dedicated research

Create, deliver, and scale material insights on sustainability.

Integrated process

Integrate Environmental, Social and Governance insights and data across asset classes and investment styles.

Sustainable solutions

Deliver sustainable solutions to help clients achieve their financial objectives.

Investment stewardship

Engage companies on sustainability issues that impact long-term performance.

ESG Investment Statements This information should not be relied upon as research, investment advice, or a recommendation regarding any products, strategies, or any security in particular. This is for illustrative and informational purposes and is subject to change. It has not been approved by any regulatory authority or securities regulator. The environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”) considerations discussed herein may affect an investment team’s decision to invest in certain companies or industries from time to time. Results may differ from portfolios that do not apply similar ESG considerations to their investment process.

Our investment capabilities

Defined contribution plans are becoming the primary way most people in the UK save for retirement. Our dedicated BlackRock defined contribution team can help you design a plan that’s built to achieve members’ retirement goals.

Target date strategies

Case study

Client Objective

The client’s primary objectives were twofold: they wished to evolve their default allocation and to simplify how the end result was presented to scheme members.

BlackRock Solution

Working closely with the client, platform and the consultant, BlackRock developed a glidepath, launched locally domiciled alternative investment funds, and delivered a structured solution for the client. The alternative investment funds are blended to provide target date funds, simplifying presentation to the scheme members, while maintaining all necessary sophistication under the hood.

As the scheme continues to grow, BlackRock continues its close relationship with the client to evolve the asset allocation over time.

Case studies are for illustrative purposes only; they are not meant as a guarantee of any future results or experience and should not be interpreted as advice or a recommendation.

Source: BlackRock as of September 25, 2023. (for case study)

Fixed Income

BlackRock offers a comprehensive fixed income platform, managing assets across the entire fixed income spectrum – from public to private, fundamental & systematic, active & index – to help deliver better outcomes, convenience, value, and transparency for our clients.

Multi-Asset Strategies and Solutions (MASS)

We help clients create customised portfolios to meet their end goals. Clients access the breadth of BlackRock’s platform, including our index, factor, alpha-seeking, and open-architecture capabilities.

Index investing

For UK institutional investors, the indexing landscape has evolved considerably over the past decades. Extracting every unit of return for a given amount of risk is crucial, and barbelling of asset allocation across index and more complex alphas such as private markets is a trend that continues to deepen.

Long-Term Asset Fund (LTAF)

LTAFs are designed with a diversified approach to alternatives in mind, providing schemes members with access to alternatives throughout the liquidity spectrum.

Rewiring

Retirement

Latest insights

Meet our team

BlackRock’s deep expertise in defined contribution, investments and solutions allows us to work in close partnership with clients to deliver better retirement outcomes.