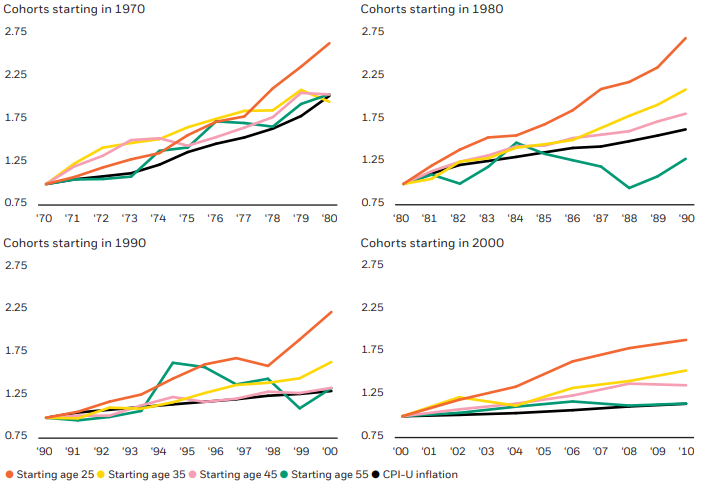

Given sufficient time, which a 25-year old most likely has, wages and asset growth are very likely to overcome losses due to an inflation shock. On the other hand, if they did have an explicit inflation hedge in place, they may face a different kind of risk: opportunity cost.

The cost of inflation hedging

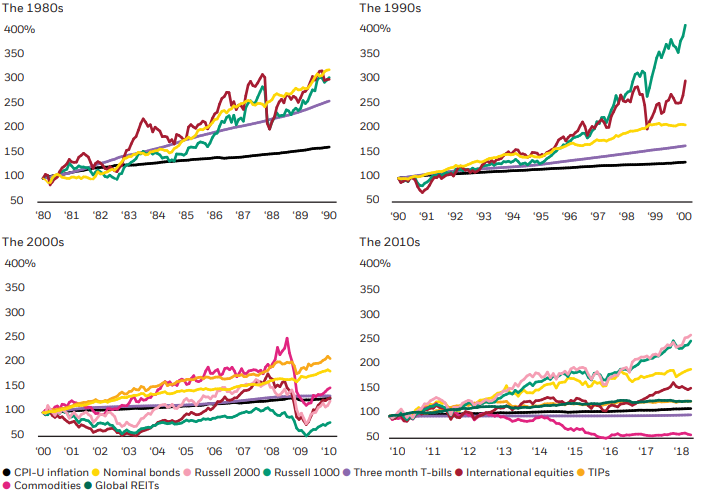

Financial assets that are generally considered to be good inflation hedges, such as commodities, REITs and TIPS, are also generally considered to have modest, and in some cases, no real return expectations over time. In order to protect against inflation shocks, they would need to be held consistently in the portfolio. (That is, unless an investor hopes to move in and out of the asset class based on their inflation expectations.)

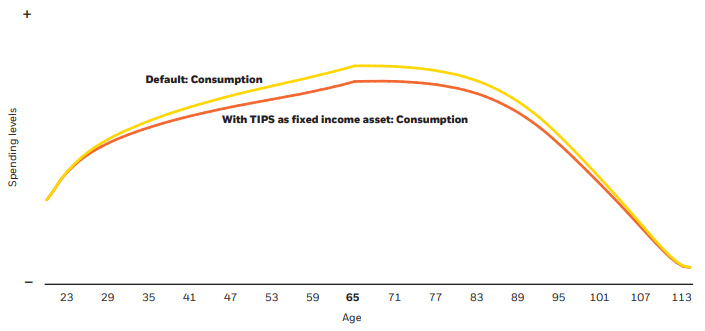

Therefore, our 25-year old would be giving up decades of potential returns to protect against a point in time inflation shock that would likely be overcome given sufficient time. That cost may not only reduce consumption during retirement (by having less financial capital due to lower returns), it may also reduce consumption during their working years since they will need to save more to offset some of the shortfall.

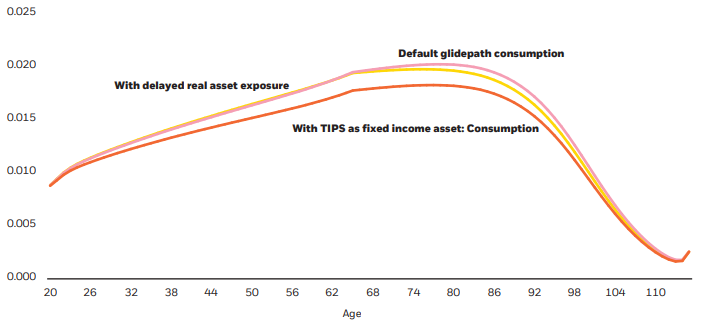

The following chart compares expected lifetime consumption based on our framework’s default assumptions, against the expected consumption that assumes a persistent allocation to TIPS, a sample inflation hedging asset, displacing some of the fixed income portfolio. This projection shows as much as 10% less consumption across the lifecycle.

Persistent inflation hedging may reduce lifetime spending