BLACKROCK INVESTMENT INSTITUTE

Mega forces: An investment opportunity

Mega forces are big, structural changes that affect investing now - and far in the future. This creates major opportunities - and risks - for investors.

BLACKROCK SUSTAINABILITY

Please read this page before proceeding as it explains certain restrictions imposed by law on the distribution of this information and the jurisdictions in which our products and services are authorised to be offered or sold.

By entering this site, you are agreeing that you have reviewed and agreed to the terms contained herein, including any legal or regulatory restrictions, and have consented to the collection, use and disclosure of your personal data as set out in the Privacy section referred to below.

By confirming below, you also acknowledge that you:

(i) have read this important information;

(ii) agree your access to this website is subject to the disclaimer, risk warnings and other information set out herein; and

(iii) are the relevant sophistication level and/or type of audience intended for your respective country or jurisdiction identified below.

The information contained on this website (this “Website”) (including without limitation the information, functions and documents posted herein (together, the “Contents”) is made available for informational purposes only.

No Offer

The Contents have been prepared without regard to the investment objectives, financial situation, or means of any person or entity, and the Website is not soliciting any action based upon them.

This material should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation or an offer or solicitation to buy or sell securities and does not constitute an offer or solicitation in any jurisdiction where or to any persons to whom it would be unauthorized or unlawful to do so.

Access Subject to Local Restrictions

The Website is intended for the following audiences in each respective country or region: In the U.S.: public distribution. In Canada: public distribution. In the UK and outside the EEA: professional clients (as defined by the Financial Conduct Authority or MiFID Rules) and qualified investors only and should not be relied upon by any other persons. In the EEA, professional clients, qualified clients, and qualified investors. For qualified investors in Switzerland, qualified investors as defined in the Swiss Collective Investment Schemes Act of 23 June 2006, as amended. In DIFC: 'Professional Clients’ and no other person should rely upon the information contained within it. In Singapore, public distribution. In Hong Kong, public distribution. In South Korea, Qualified Professional Investors (as defined in the Financial Investment Services and Capital Market Act and its sub-regulations). In Taiwan, Professional Investors. In Japan, Professional Investors only (Professional Investor is defined in Financial Instruments and Exchange Act). In Australia, public distribution. In China, this may not be distributed to individuals resident in the People's Republic of China ("PRC", for such purposes, excluding Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan) or entities registered in the PRC unless such parties have received all the required PRC government approvals to participate in any investment or receive any investment advisory or investment management services. For Other APAC Countries, Institutional Investors only (or professional/sophisticated /qualified investors, as such term may apply in local jurisdictions). In Latin America, institutional investors and financial intermediaries only (not for public distribution).In Latin America, no securities regulator within Latin America has confirmed the accuracy of any information contained herein. The provision of investment management and investment advisory services is a regulated activity in Mexico thus is subject to strict rules. For more information on the Investment Advisory Services offered by BlackRock Mexico please refer to the Investment Services Guide available at www.blackrock.com/mx.

This Contents are not intended for, or directed to, persons in any countries or jurisdictions that are not enumerated above, or to an audience other than as specified above.

This Website has not been, and will not be submitted to become, approved/verified by, or registered with, any relevant government authorities under the local laws. This Website is not intended for and should not be accessed by persons located or resident in any jurisdiction where (by reason of that person's nationality, domicile, residence or otherwise) the publication or availability of this Website is prohibited or contrary to local law or regulation or would subject any BlackRock entity to any registration or licensing requirements in such jurisdiction.

It is your responsibility to be aware of, to obtain all relevant regulatory approvals, licenses, verifications and/or registrations under, and to observe all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction in connection with your access. If you are unsure about the meaning of any of the information provided, please consult your financial or other professional adviser.

No Warranty

The Contents are published in good faith but no advice, representation or warranty, express or implied, is made by BlackRock or by any person as to its adequacy, accuracy, completeness, reasonableness or that it is fit for your particular purpose, and it should not be relied on as such. The Contents do not purport to be complete and is subject to change. You acknowledge that certain information contained in this Website supplied by third parties may be incorrect or incomplete, and such information is provided on an "AS IS" basis. We reserve the right to change, modify, add, or delete, any content and the terms of use of this Website without notice. Users are advised to periodically review the contents of this Website to be familiar with any modifications. The Website has not made, and expressly disclaims, any representations with respect to any forward-looking statements. By their nature, forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties because they relate to events and depend on circumstances that may or may not occur in the future.

No information on this Website constitutes business, financial, investment, trading, tax, legal, regulatory, accounting or any other advice. If you are unsure about the meaning of any information provided, please consult your financial or other professional adviser.

No Liability

BlackRock shall have no liability for any loss or damage arising in connection with this Website or out of the use, inability to use or reliance on the Contents by any person, including without limitation, any loss of profit or any other damage, direct or consequential, regardless of whether they arise from contractual or tort (including negligence) or whether BlackRock has foreseen such possibility, except where such exclusion or limitation contravenes the applicable law.

You may leave this Website when you access certain links on this Website. BlackRock has not examined any of these websites and does not assume any responsibility for the contents of such websites nor the services, products or items offered through such websites.

Intellectual Property Rights

Copyright, trademark and other forms of proprietary rights protect the Contents of this Website. All Contents are owned or controlled by BlackRock or the party credited as the provider of the Content. Except as expressly provided herein, nothing in this Website should be considered as granting any licence or right under any copyright, patent or trademark or other intellectual property rights of BlackRock or any third party.

This Website is for your personal use. As a user, you must not sell, copy, publish, distribute, transfer, modify, display, reproduce, and/or create any derivative works from the information or software on this Website. You must not redeliver any of the pages, text, images, or content of this Website using "framing" or similar technology. Systematic retrieval of content from this Website to create or compile, directly or indirectly, a collection, compilation, database or directory (whether through robots, spiders, automatic devices or manual processes) or creating links to this Website is strictly prohibited. You acknowledge that you have no right to use the content of this Website in any other manner.

Additional Information

Investment involves risks. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and the income from them can fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed. You may not get back the amount originally invested. Changes in the rates of exchange between currencies may cause the value of investments to diminish or increase.

Privacy

Your name, email address and other personal details will be processed in accordance with BlackRock’s Privacy Policy for your specific country which you may read by accessing our website at https://www.blackrock.com.

Please note that you are required to read and accept the terms of our Privacy Policy before you are able to access our websites.

Once you have confirmed that you agree to the legal information herein, and the Privacy Policy – by indicating your consent – we will place a cookie on your computer to recognise you and prevent this page from reappearing should you access this site, or other BlackRock sites, on future occasions. The cookie will expire after six months, or sooner should there be a material change to this important information.

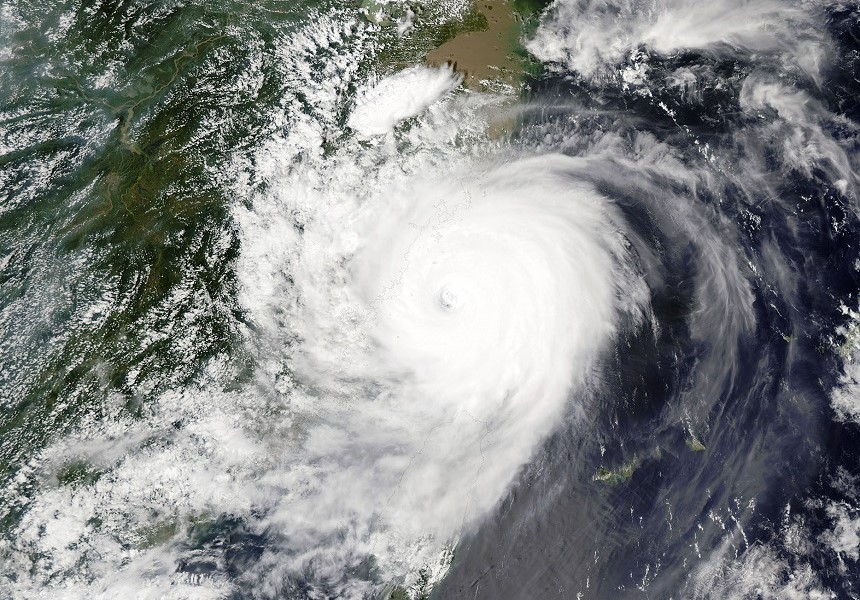

The global BlackRock Geopolitical Risk Indicator (BGRI) aims to capture overall market attention to geopolitical risks, as the line chart shows. The indicator is a simple average of our top-10 risks.

We see the geopolitical environment shaped by shifts that are redefining global political and economic relationships. These include the U.S. resetting trade deals, industrial policy and alliances, intensifying U.S.–China competition with AI at its core and continued volatility from conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza and the Caribbean.

Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute. Views and data as of December 2025. Notes: The “risks” column lists the 10 key geopolitical risks that we track. The “description” column defines each risk. “Attention score” reflects the BlackRock Geopolitical Risk Indicator (BGRI) for each risk. The BGRI measures the degree of the market’s attention to each risk, as reflected in brokerage reports and financial media. See the "how it works" section on p.7 for details. The table is sorted by the “Likelihood” column which represents our fundamental assessment, based on BlackRock’s subject matter experts, of the probability that each risk will be realized – either low, medium or high – in the near term. The “our view” column represents BlackRock’s most recent view on developments related to each risk. This is not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. This information should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any funds or security in particular. Individual portfolio managers for BlackRock may have opinions and/or make investment decisions that may, in certain respects, not be consistent with the information contained herein.

We have developed a market movement score for each risk that measures the degree to which asset prices have moved similarly to our risk scenarios, integrating insights from our Risk & Quantitative Analysis (RQA) team and their Market-Driven Scenario (MDS) shocks. We do this by estimating how “similar” the current market environment is to our expectation of what it would look like in the event the particular MDS was realized, also taking into account the magnitude of market moves. The far right of the horizontal axis indicates that the similarity between asset movements and what our MDS assumed is greatest; the middle of the axis means asset prices have shown little relationship to the MDS, and the far left indicates markets have behaved in the opposite way that our MDS anticipated.

Risk map

BlackRock Geopolitical market attention, market movement and likelihood

How to gauge the potential market impact of each of our top-10 risks? We have identified three key “scenario variables” for each – or assets that we believe would be most sensitive to a realization of that risk. The chart below shows the direction of our assumed price impact.

| Risk | Asset | Direction of assumed price impact |

|---|---|---|

| Global trade protectionism | U.S. specialty retail & distribution |  |

| U.S. consumer durables & apparel |  |

|

| U.S. two-year Treasury |  |

|

| Middle East regional war | Brent crude oil |  |

| VIX |  |

|

| U.S. high yield credit |  |

|

| U.S.-China strategic competition | Taiwanese dollar |  |

| Taiwanese equities |  |

|

| China high yield |  |

|

| Global technology decoupling | Chinese yuan |  |

| Chinese semiconductors |  |

|

| U.S. semiconductors and electrical equipment |  |

|

| Major cyber attack(s) | U.S. high yield utilities |  |

| U.S. dollar |  |

|

| U.S. utilities sector |  |

|

| Major terror attack(s) | Germany 10-year government bond |  |

| Japanese yen |  |

|

| Europe airlines sector |  |

|

| Russia-NATO conflict | Russian equities |  |

| Russian ruble |  |

|

| Brent crude oil |  |

|

| Emerging markets political crisis | Latin America consumer staples sector |  |

| Emerging vs. developed equities |  |

|

| Brazil debt |  |

|

| North Korea conflict | Japanese yen |  |

| Korean won |  |

|

| Korean equities |  |

|

| European fragmentation | EMEA hotels & leisure |  |

| Italy 10-year government bond |  |

|

| Russian ruble |  |

Source: BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from BlackRock’s Aladdin Portfolio Risk Tools application, December 2025. Notes: The table depicts the three assets that we see as key variables for each of our top-10 geopolitical risks – as well as the direction of the assumed shocks for each in the event of the risk materializing. The up arrow indicates a rise in prices (corresponding to a decline in yields for bonds); the down arrow indicates a fall in prices. Our analysis is based on similar historical events and current market conditions such as volatility and cross-asset correlations. See the “implied stress testing framework” section of the 2018 paper Market-Driven Scenarios: An Approach for Plausible Scenario Construction for details. For illustrative purposes only. The scenarios are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect all possible outcomes as geopolitical risks are ever-evolving. This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. This information should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any funds, strategy or security in particular.

We detail the key geopolitical events over the next year in the table below.

| Date | Location | Event |

|---|---|---|

| January 2026 | ||

| Jan 19–23 | Switzerland | World Economic Forum Annual Meeting (Davos) |

| Jan 22–23 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

| Jan 27–28 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| February 2026 | ||

| Feb (TBC) | Bangladesh | General elections |

| Feb 4–5 | Euro area | ECB Governing Council monetary policy meeting (Frankfurt) |

| Feb 5 | United Kingdom | BOE Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting |

| Feb 13–15 | Germany | Munich Security Conference (Munich) |

| March 2026 | ||

| Mar 17–18 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Mar 18–19 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting (Frankfurt) |

| Mar 18–19 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

| Mar 19 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| April 2026 | ||

| April 2026 | U.S.-China | Potential China visit by President Trump |

| Apr 12 | Peru | Presidential & Congressional General Election |

| Apr 13–18 | United States | IMF & World Bank Group Spring Meetings (Washington, DC) |

| Mid-April (TBC) | United States | G20 Finance Ministers & Central Bank Governors’ Meeting (on margins of Spring Meetings, dates TBC) |

| Apr 27–28 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

| Apr 28–29 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Apr 29–30 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting (Frankfurt) |

| Apr 30 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| May 2026 | ||

| Late May / early June (TBC) | Singapore | Shangri-La Dialogue Asia Security Summit (dates TBC) |

| May / June (TBC) | France | OECD Ministerial Council Meeting (Paris, dates TBC) |

| May 31 | Colombia | Presidential Election |

| June 2026 | ||

| June / July TBC | U.S.-China | Potential U.S. trip by President Xi |

| Jun 10–11 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting |

| Jun 14–16 | France | G7 Leaders’ Summit (Évian-les-Bains) |

| Jun 15–16 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

| Jun 16–17 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Jun 18 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| July 2026 | ||

| Jul 7–8 | Türkiye | NATO Leaders’ Summit (Ankara) |

| July (TBC) | India | 18th BRICS Leaders’ Summit (India chair; host city/dates TBC) |

| Jul 22–23 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting |

| Jul 28–29 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Jul 30 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| Jul 30–31 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

| August 2026 | ||

| Early Aug (TBC) | G20 | Finance Ministers & Central Bank Governors’ Meeting (standalone FMCBG) |

| Late Aug (dates TBC) | United States | Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium (Jackson Hole, Wyoming) |

| September 2026 | ||

| Sep 8 | United States | Opening of 81st Session of the UN General Assembly (UNGA 81), New York |

| Sep 9–10 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting (hosted by Deutsche Bundesbank) |

| Sep 15–16 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Sep 17 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| Sep 17–18 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

| Sep 22–29 (TBC) | United States | UNGA 81 High-Level Week / General Debate (New York) |

| October 2026 | ||

| Oct 4 | Brazil | First round of Brazilian general elections (presidential, congressional, gubernatorial) |

| Oct 12–18 | Thailand | IMF & World Bank Group Annual Meetings (Bangkok) |

| Mid-October (TBC) | Thailand | G20 Finance Ministers & Central Bank Governors’ Meeting (on margins of Annual Meetings, dates TBC) |

| Oct 25 | Brazil | Possible second-round presidential vote (if needed) |

| Oct 27–28 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Oct 28–29 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting |

| November 2026 | ||

| Nov 3 | United States | U.S. midterm elections (Congressional and state-level races) |

| Nov 5 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| Nov 9–20 | Türkiye | UN Climate Change Conference (COP31), Antalya |

| November (TBC) | China | APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting, Shenzhen |

| December 2026 | ||

| Dec 8–9 | United States | FOMC Meeting |

| Dec 14–15 | United States | G20 Leaders’ Summit (U.S. G20 presidency year), Doral, Florida |

| Dec 16–17 | Euro area | ECB monetary policy meeting |

| Dec 17 | United Kingdom | BOE MPC meeting |

| Dec 17–18 | Japan | BOJ Monetary Policy Meeting |

Source: BlackRock Investment Institute, December 2025.

The quantitative components of our geopolitical risk dashboard incorporate two different measures of risk: the first based on the market attention to risk events, the second on the market movement related to these events.

The BlackRock Geopolitical Risk Indicator (BGRI) tracks the relative frequency of brokerage reports (via Refinitiv) and financial news stories (Dow Jones News) associated with specific geopolitical risks. We adjust for whether the sentiment in the text of articles is positive or negative, and then assign a score. This score reflects the level of market attention to each risk versus a 5-year history. We assign a heavier weight to brokerage reports than other media sources since we want to measure the market's attention to any particular risk, not the public’s.

Our updated methodology improves upon traditional “text mining” approaches that search articles for predetermined key words associated with each risk. Instead, we take a big data approach based on machine-learning. Huge advances in computing power now make it possible to use language models based on neural networks. These help us sift through vast data sets to estimate the relevance of every sentence in an article to the geopolitical risks we measure.

How does it work? First we “train” the language model with broad geopolitical content and articles representative of each individual risk we track. The pre-trained language model then focuses on two tasks when trawling though millions of brokerage reports and financial news stories:

The attention and sentiment scores are aggregated to produce a composite geopolitical risk score. A zero score represents the average BGRI level over its history. A score of one means the BGRI level is one standard deviation above its historical average, implying above-average market attention to the risk. We weigh recent readings more heavily in calculating the average. The level of the BGRIs changes slowly over time even if market attention remains constant. This is to reflect the concept that a consistently high level of market attention eventually becomes “normal.”

Our language model helps provide more nuanced analysis of the relevance of a given article than traditional methods would allow. Example: Consider an analyst report with boilerplate language at the end listing a variety of different geopolitical risks. A simple keyword-based approach may suggest the article is more relevant than it really is; our new machine learning approach seeks to do a better job at adjusting for the context of the sentences – and determining their true relevance to the risk at hand.

In the market movement measure, we use Market-Driven Scenarios (MDS) associated with each geopolitical risk event as a baseline for how market prices would respond to the realization of the risk event.

Our MDS framework forms the basis for our scenarios and estimates of their potential one-month impact on global assets. The first step is a precise definition of our scenarios – and well-defined catalysts (or escalation triggers) for their occurrence. We then use an econometric framework to translate the various scenario outcomes into plausible shocks to a global set of market indexes and risk factors.

The size of the shocks is calibrated by various techniques, including analysis of historical periods that resemble the risk scenario. Recent historical parallels are assigned greater weight. Some of the scenarios we envision do not have precedents – and many have only imperfect ones. This is why we integrate the views of BlackRock’s experts in geopolitical risk, portfolio management, and Risk and Quantitative Analysis into our framework. See the 2018 paper Market Driven Scenarios: An Approach for Plausible Scenario Construction for details. MDS are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect all possible outcomes as geopolitical risks are ever-evolving.

We then compile a market movement index for each risk.* This is composed of two parts:

These two measures are combined to create an index that works as follows:

*This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. This information should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any funds, strategy or security in particular. The scenarios are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect all possible outcomes as geopolitical risks are ever-evolving.

On October 8, Israel and Hamas agreed to a multi-phase peace plan negotiated by the U.S. and later endorsed by the UN Security Council. Initial steps, including hostage and prisoner exchanges and the pullback of Israeli forces outside major Palestinian population centers, have largely held. We think a lasting settlement that fully disarms Hamas and stabilizes Gaza will be difficult to achieve. The regional balance has shifted with the fall of the Assad regime in Syria, Israel’s degradation – but not elimination – of Iran-backed proxies such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and Iran’s diminished ability to defend itself following its 12-day war with Israel in June. Risks of renewed escalation remain elevated as Iran and its proxies seek to reconstitute, and as Israel continues military operations action against them. The Gulf is consolidating political and economic influence, and U.S. ties are deepening, including September security guarantees to Qatar and November defense and technology agreements with Saudi Arabia.

AI is at the center of U.S.-China strategic competition, with its enabling physical infrastructure increasingly treated as a national security asset. The U.S. administration is seeking to turbocharge AI development and the global diffusion of U.S. technologies. It is pursuing advances in artificial general intelligence by scaling compute capacity and building more powerful foundational models, while China focuses on widespread adoption through downstream technologies like robotics, drones and electric vehicles (EVs). The U.S. administration continues to promote the diffusion of U.S. AI technology globally, including to Gulf countries and to China. President Trump approved the sale of NVIDIA's H200 chips to China, siding with advisors who favor expanding market share for U.S. AI companies despite national security objections. While this sets positive conditions for further talks with Beijing during 2026, we think China will maintain its strategic focus on self-reliance and building out an indigenous Chinese AI ecosystem.

Mounting geopolitical competition is fueling a surge in cyber attacks that are growing in scope, scale and sophistication. Around the world, new AI technologies are enabling criminal actors to identify vulnerable targets, craft convincing scams and generate malicious code at unprecedented speed. In November, AI firm Anthropic reported uncovering an AI-enabled cyber espionage campaign in which state-backed hackers used its systems to target more than 30 companies and foreign governments, with AI automating up to 90% of the operation. The proliferation of new AI models has also raised concerns over their vulnerability to hacking and manipulation, prompting alarm in national security circles. State-backed hacking remains a significant risk, increasingly focused on political espionage, infecting critical infrastructure with malware and large-scale theft of intellectual property.

The threat of terrorism against U.S. interests remains at an extraordinarily high level. U.S. officials have described the November shooting of two National Guard members as an act of terror and U.S. agencies continue to highlight the persistent motivation by extremist groups to conduct or inspire attacks abroad. We also see risks stemming from sustained instability in the Middle East and across Africa, where jihadist groups have advanced towards the capital cities of Mali and Somalia, raising the threat of broader political control. Closer to the U.S., the U.S. administration has intensified its focus on Latin American drug cartels designated as terrorist organizations. Since September, the U.S. has carried out military strikes on vessels it alleged to be carrying cartel members. In November, it designated Cartel de Soles, a group it claims to be headed by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. This could pave the way for broader U.S. action against Venezuela after months of regional military buildup.

Since imposing historically high tariffs on over 90 countries in August, the U.S. administration has continued to pursue an aggressive approach to trade policy through new deals and pledges of inbound investment into the U.S. We think the period of peak disruption may have passed as the administration has rolled out exemptions and carve-outs for certain countries, companies and sectors, including food and agricultural goods. Ongoing Section 232 investigations could still result in additional sector-specific tariffs, we think. On November 5, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case testing the administration’s ability to impose global “reciprocal” tariffs under emergency authorities, with a decision expected by early 2026. If those tariffs are struck down, we expect the administration to rely on alternative authorities to reconstitute much of its tariff program. Despite a temporary trade truce with China (see U.S.-China strategic competition risk below), we expect rolling negotiations, agreements and disputes to be the new normal in trade.

On October 30, President Trump and President Xi met in South Korea for the first time since 2019. Both countries agreed to a one-year trade truce under which the U.S. will reduce tariffs on select Chinese goods and China will delay the implementation of a broad rare earth export control regime, among other measures. The leaders also agreed to hold an April summit in Beijing and additional meetings in 2026, which we think will encourage both countries to avoid renewed disruption in the near term. Even so, competition with China remains at the core of nearly every major U.S. policy, and both countries have demonstrated their willingness to use strategic dependencies in areas such as rare earths and advanced technology. In the military sphere, the U.S. national security team remains focused on countering China in the Indo-Pacific. We think regional tensions will remain structurally high, with Sino-Japanese tensions spiking following November comments by Japan’s new Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Taiwan and an aggressive and adverse response from Beijing.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine remains the largest and most dangerous military conflict in Europe since World War Two. Negotiations – including U.S. engagement aimed at a peace plan, security guarantees and post-war reconstruction – have intensified, but Russian escalations and maximalist demands may continue to challenge a durable settlement. In the meantime, the war of attrition continues, and the conflict has escalated. Ukraine continues to face large-scale Russian drone and missile attacks on urban areas and energy infrastructure and has retaliated with sustained strikes on Russian energy export facilities and military targets, including its first use of U.S.-supplied long-range missiles in November. Russia continues to test European resolve through ongoing grey-zone operations, to which European governments have signaled plans for a stronger response.

A wave of youth-led protest movements has swept across several emerging markets in recent months, including Bulgaria, Morocco, Kenya, Indonesia, Peru, the Philippines, Nepal and Madagascar. These movements have produced varied outcomes, from the resignation of Nepal’s prime minister following army-mediated negotiations to the forced exile of Madagascar’s president after a military-backed takeover. In the Philippines, protests persist over corruption allegations linked to flood-control projects that have generated billions in potential losses and already led to the resignation of two cabinet ministers. Despite differing contexts, the share common drivers, including cost-of-living pressures, youth unemployment and governance grievances. We are watching for further unrest ahead of a fresh cycle of global elections slated for 2026.

North Korea has taken a series of escalatory actions that heighten risks in and beyond the Asia-Pacific, including renouncing peaceful reunification with South Korea, accelerating its nuclear weapons program and deploying troops and munitions to support Russia’s war in Ukraine. In October, North Korea fired multiple short-range ballistic missiles and conducted hypersonic weapons, its first launches since May and the first since South Korean President Lee Jae Myung took office in June. President Trump has reiterated his desire to reengage North Korean leader Kim Jong Un through personal diplomacy, most recently during his October trip to Asia. President Lee has encouraged this approach, reflecting his own interest in easing tensions with Pyongyang. Compared with President Trump’s first term, however, Pyongyang appears emboldened by its stronger ties with Russia and China, as well as its own military advances, and may be less inclined to pursue better relations with the U.S.

We’ve seen a reset of the U.S.-Europe relationship since the start of the second Trump administration, outlined starkly in the Administration’s National Security Strategy. European governments, focused on pursuing "strategic autonomy,” have announced ambitious defense spending and economic reform agendas, drawing in part on the Draghi report on EU competitiveness to guide policy. We think delivery risks remain high amid fiscal, industrial and bureaucratic constraints. Political dynamics have also shifted, with headline risks no longer about outright rejection of the European project but rather about growing political paralysis within EU member states. Populist parties – now more broadly anti-incumbent than anti-EU – have narrowed governing majorities and reduced policy flexibility. Their rise reflects disillusionment with mainstream coalitions and erodes the consensus needed for large-scale reforms. This new cycle of constrained policymaking – compounded by a fragile governing majority in France and a narrow coalition in Germany – could limit Europe’s ability to address its security and competitiveness challenges heading into 2026.