If you’re familiar with exchanged traded funds, or ETFs, you may have heard the phrase Creation and Redemption. But let’s dig deeper into what it means and why it’s important?

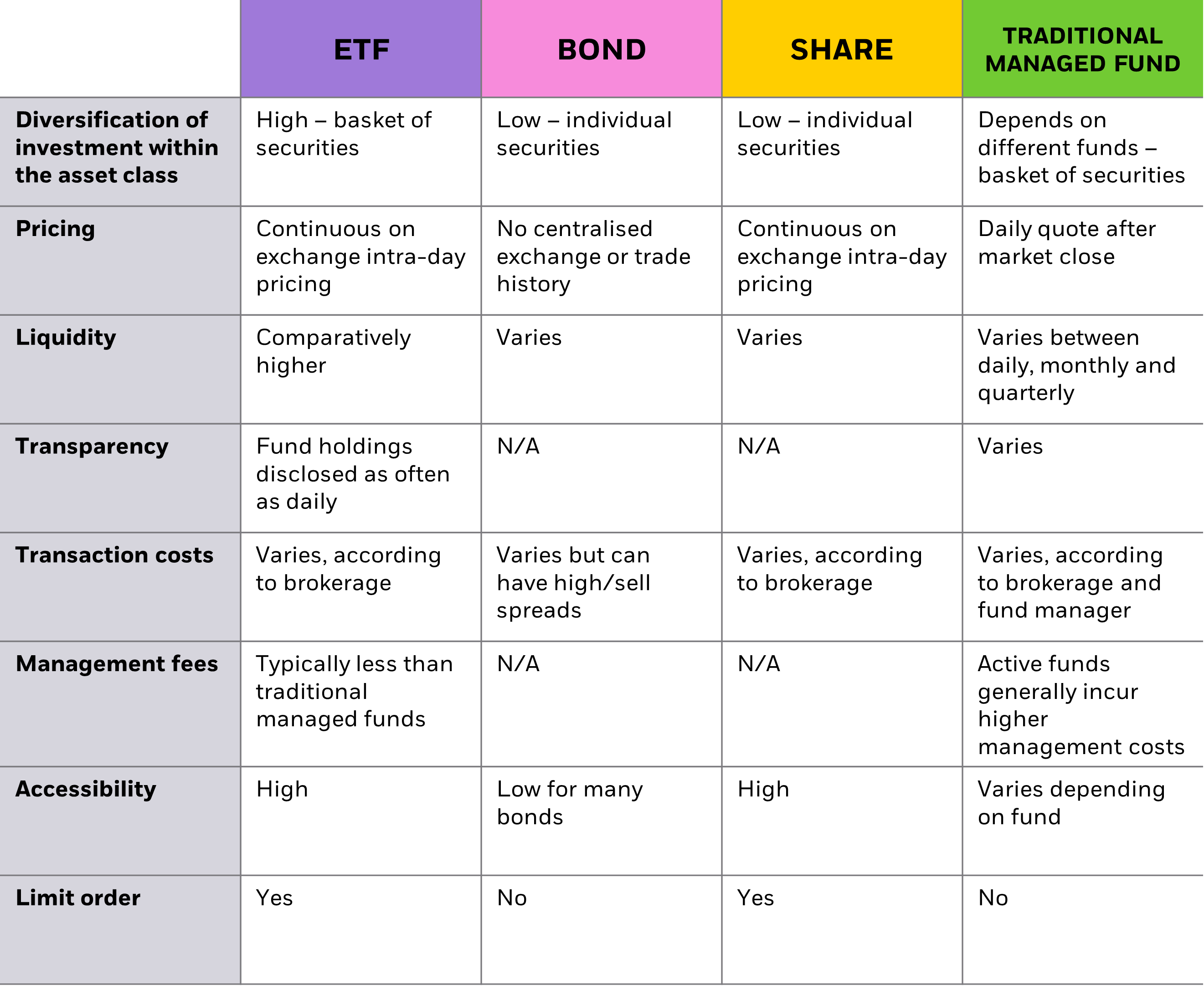

ETFs are low-cost ways to access both broad and precise market exposures. They trade like stocks, can provide deep liquidity, and their prices are closely tied to the value of their underlying securities. But how is this possible? It’s all thanks to the processes of creation and redemption.

To better understand how it works, think of an individual stock or bond as a flower. Just like companies come in different sectors and sizes, flowers come in all kinds of varieties and shapes. Now take a variety of flowers and bundle them into a bouquet, and you’ve got yourself an ETF. The price of an ETF is based on the price of the stocks or bonds that make up the ETF. So when the prices of individual flowers increase, so does the price of the bouquet.

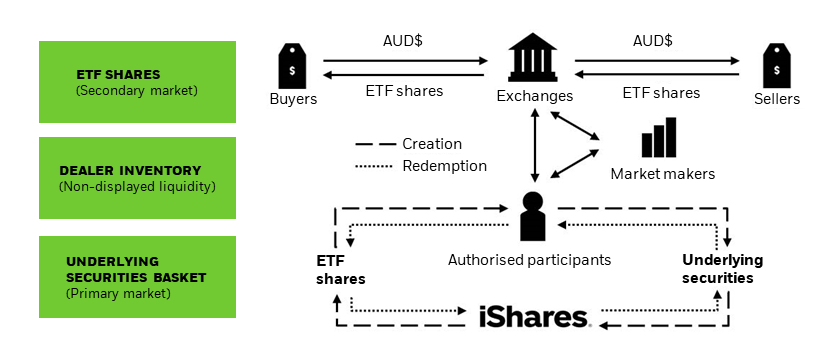

Now let’s say an investor wants to buy a bouquet, what does she do? She goes to a flower shop, which we can imagine as a brokerage firm. Here, the investor browses bouquets and finds the emerging markets bouquet, the clean energy bouquet, and the S&P 500 bouquet. She decides to buy one S&P 500 bouquet. Like a florist, the broker dealer takes this order and sends the market maker out to the market to fill it. The market maker finds the S&P 500 bouquet and brings it back to the shop. The investor pays the broker and gets the ETF she wants. Easy!

But what happens if the investor wants one hundred bouquets? Just as before, the broker dealer sends the market maker to get one hundred bouquets. But there are only five bouquets available. So what’s the poor market maker to do? Thanks to the unique process of ETF creation, more bouquets can be made to fill the large order. The creation process kicks in as soon as the investor places the order. It begins with the authorised participant, or AP for short. The AP watches the market in order to manage the supply of flowers and bouquets. When the market maker can’t fill an order, he asks the AP to make extra bouquets. The AP checks the S&P 500 Index to find out exactly which individual flowers make up the S&P 500 bouquet. Once the AP has everything he needs, he gives the flowers to iShares. Similar to a bouquet designer, iShares assembles brand-new S&P 500 bouquets. Once they bundle the individual flowers, iShares gives the new bouquets back to the AP; the AP gives the bouquets to the market maker; and the market maker brings them back to the broker dealer,

who in turn sells them to the investor at market price. Despite the size of the order, the price of the bouquets stays approximately the same due to the increased supply.

Now let’s flip things around for redemption.

The investor wants to return one hundred bouquets, so the florist buys them back. He then gets the market maker to take the bouquets to the market to see who wants them. But there’s already an adequate supply of bouquets. So what does the market maker do now? Well, he turns to the AP again. The market maker gives the AP the bouquets, who then brings them to the iShares workshop where they are disassembled into individual flowers. And just like that, the number of bouquets decreases to meet market needs and keep bouquet prices stable. Creation and redemption occur to keep ETF supply in line with demand. This generally keeps ETF values closely tied to their underlying assets. And it allows you to easily trade ETFs throughout the day due to their deep liquidity. Visit iShares to learn more about ETFs today.